The percentage of the population in Iceland’s largest church body, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland, dropped from 90 percent in the 1990s to 64 percent now. But other groups are growing. … It’s mostly native Icelanders who are joining the ranks of Ásatrú [Neo-Paganism], which tripled in size from 2007 to 2017. – Julia Duin

The percentage of the population in Iceland’s largest church body, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland, dropped from 90 percent in the 1990s to 64 percent now. But other groups are growing. … It’s mostly native Icelanders who are joining the ranks of Ásatrú [Neo-Paganism], which tripled in size from 2007 to 2017. – Julia Duin

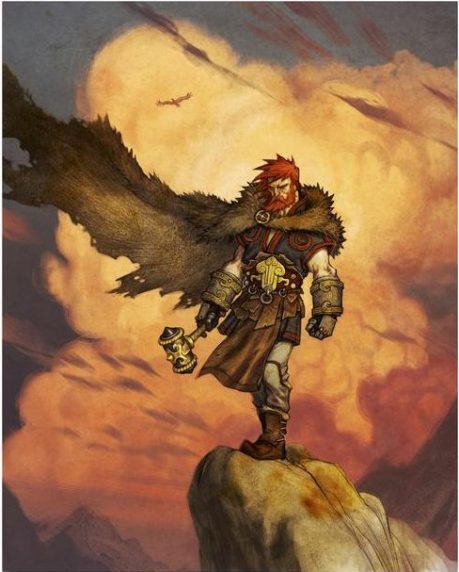

The old Norse gods got to come out and play this week in Iceland during a fall equinox observance in honor of the likes of Thor, Odin, Freya, Frigg, Var, Freyr and Loki.

On Wednesday night, 52 people gathered on a farm about 30 miles north of Reykjavik, on the shores of Hvalfjörður Bay, a serene body of water banked by mossy green hillsides sweeping up into fog-topped mountains. Directly south was Mount Esja, actually a volcanic range overlooking Reykjavik, the country’s capital. Rain from the day before had moved on, and the evening was clear and still.

Presiding was Jóhanna Harðardóttir, a priestess in Ásatrúarfélagið, known internationally as Ásatrú, Iceland’s fastest-growing religion—or spiritual movement. She began by hoisting a bull’s horn containing honey mead to the local goddesses, asking for blessings for the coming winter.

As a heathen movement first practiced by the early Vikings who trolled Iceland’s eastern shores, Ásatrú was resurrected from a 1,000-year sleep a few decades ago. Variations of it have appeared in numerous other countries, some of it embraced by neo-Nazi groups that have appropriated Ásatrú’s runes and Norse symbols.

But the Icelanders who founded the movement have no interest in a Viking-centric political movement. Their main preference is to get a planned temple near downtown Reykjavik up and running—an effort that, with cost overruns and COVID-19 complications, has stalled. But once more money is raised, the temple will be built, with features including a circular glass roof to give the effect of being out in nature.

Until then, Harðardóttir, 69, hosts gatherings at her waterfront farm. Wednesday’s ceremony, called a blót (pronounced like “bloat”), began with a walk through a grassy pasture to a circle of grass-covered mounds with four narrow openings. They were roughly 6 feet tall. Inside was a circular space, about 18 feet in diameter, with a gravel floor.

Four benches lined the circle. Near one bench was a 4-foot-high block of curved wood intended as a phallic symbol. Set in one of the mounds was a stone figure with large breasts and a distended belly: the fertility goddess Freya.

In the middle was a metal brazier set over rocks, next to which was a 2-foot-high stone with a six-petaled flower on one side. On the other side was a hammer symbol for the god Thor.

“This is my favorite god,” Harðardóttir said. “He protects me, and I talk to him. We talk to the gods. They are just like us. They have quarrels like you and me.”

And so for Thor—and any other deities who could have been listening in—the priestess sanctified the area and chanted verses from the Prose Edda, a compilation of Norse mythology by 12th-century chieftain Snorri Sturluson. A fire was lit in the brazier.

Wearing a green cape over a blue woolen gown with silver broaches, Harðardóttir passed around the horn. Because of COVID, no one took a sip.

“COVID,” she said, sighing, “makes things so boring.”

What’s not boring are the statistics. The percentage of the population in Iceland’s largest church body, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland, dropped from 90 percent in the 1990s to 64 percent now. But other groups are growing. There are at least 1,000 Muslims in the country, and the arrival in 2018 of the country’s first full-time Jewish leader, Brooklyn, New York Rabbi Avi Feldman, has spurred an increase in Jewish adherents. Mostly because of immigration from majority-Catholic countries such as Poland, the number of Catholics has jumped from 3,200 in 1998 to 14,658 members in 2019.

But it’s mostly native Icelanders who are joining the ranks of Ásatrú, which tripled in size from 2007 to 2017. Once the temple, which has been beset with cost overruns, opens, more will come through the doors.

“We’re over budget,” Harðardóttir admitted, “but we owe no one. We gain every year, but it’s not because we are trying. People come to our ceremonials and ask, ‘Why didn’t I know about this before?'”

The group does not proselytize, nor does it insist on a dress code for events. Presenters tend to have on some sort of robe, but the rest can dress according to the weather (which, this being Iceland, is usually cold and rainy). They can take their pick of whichever gods they have need of.

Besides the war god Odin, Freya and the trickster god Loki (“He steals my keys,” Harðardóttir insisted), there are Odin’s wife, Frigg, and Vár, a goddess who protects contracts.

“They are so many,” she said. “When you’re in love, it’s good to have Freya. When you are sick, you want Eir [the goddess associated with healing] around.”

Her red Nissan has a “Protected by Thor” bumper sticker on its rear window.

“He has protected me. I need a lot of strength and energy,” she insisted. When she was facing the near death of a grandchild, “for three days, we didn’t know if she’d live. Thor got me through it.”

The child survived.

Asked about specifics, Harðardóttir said, “I’ve only seen his hands and his clothing. He has a very thick belt and leather-like straps around his wrists. They are amazing hands. I’ve never seen any other like them.”

She’s had this kind of communication with Thor “since I was a child.” Her mother was Catholic; the father believed nothing. Although the household was nonobservant, she underwent the Christian rite of confirmation as a teenager, which she now regrets.

“I felt bad being confirmed,” she said. “I felt bad about a God who was constantly spying on you.” Today, two of her three siblings affiliate with Ásatrú.

Ásatrú does not involve any sort of creed or set of beliefs.

“I don’t believe in a god in the sky we pray to, but I believe in him [Thor],” the priestess said. “Ásatrú is not a religion where you pray to a god. It is more like a lifestyle, living in peace with yourself and the surroundings.”

Around her neck is a “sun cross”—not a Christian symbol but a plus-shaped silver cross representing the four elements (earth, water, air and fire) placed in a circle representing eternity. “Icelanders know their sagas,” she said, adding that many feel that the old religions are truer to their national identity. “This country is still Christian in name only.”

The late University of Pennsylvania scholar Michael Fell wrote in his 1999 book, And Some Fell Into Good Soil: A History of Christianity in Iceland, that when the Icelandic Althing (one of the world’s earliest known parliaments) met in the summer of 1000, Thorgeir, a heathen chieftain and law speaker of the Althing, declared that Iceland could not exist under two different laws. Thus, the island had to convert to Christianity, starting with himself.

Thorgeir’s method—covering himself with a cloak or horsehide for 24 hours to ponder the decision—felt legitimate to his heathen companions because the oracular method was how they reached important decisions. Others have suggested that Thorgeir’s oracle was all show and that in reality he was succumbing to political pressure, as Norway was leaning on Iceland to accept Christianity.

Whatever the case, heathenism officially vanished from Iceland, not to appear until 1972, when a group of 12 Icelanders meeting at the Hotel Borg in downtown Reykjavik founded Ásatrú as a homegrown folk religion. Within a year, it was an officially recognized religious organization.

The organization has gone through several leadership changes, and Harðardóttir said she is only temporarily acting as the convener while the current high priest, Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson, is on sick leave. She said she believes the mass conversions to Christianity of a millennium ago were more of a business decision involving Icelanders’ ability to find markets for their fish with Christianized Europe.

“The thought back then was: Icelanders have 12 gods, why should we worry about one more called Jesus?” she said.

The god most honored in the Ásatrú cosmology does seem to be Thor, and Harðardóttir’s horn includes runes showing Thor as “the son of the Earth; friend and protector.” On the other side of the horn is a poem about the mead. Underneath are two ravens belonging to Odin. Those same ravens are tattooed on her arms.

For now, Ásatrú is continuing to arouse interest, even among the young. Five teenagers attended Wednesday’s rite, and for them—and other guests—Harðardóttir told the tale of Odin and Sleipnir, his mythical eight-legged horse.

She has come out with a children’s book, Sólstafir (“Sunrays”), the story of the god Freyr and his wife, Gerd. It sold well, she said, although it was only in Icelandic. Harðardóttir is planning a second one for a larger readership, in Icelandic and English, about Thor taking two human children to Asgard, home of the gods.

Children brought up in pagan ways are trained to do “what’s good for you and others,” she said. Even though Ásatrú has no concept of sin, “there are wrong things,” she added. “I don’t make rules for other people. I trust they know what’s best.”

And if they don’t?

“You can tell others what is right and wrong and teach them to learn the difference. We will have to find out how to teach each other what is best,” she said. – Newsweek, 24 September 2021

› Julia Duin is an author and contributing editor for religion for Newsweek.

Filed under: iceland | Tagged: asatru, heathenism, neo-paganism, norse gods, thor | Comments Off on Thor Is beating the Lutheran Church in a battle for believers – Julia Duin