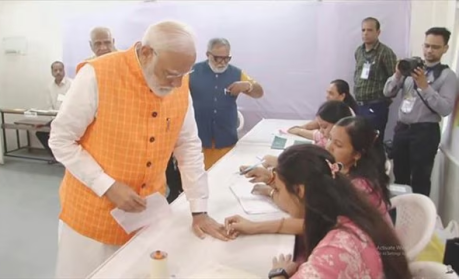

![]() India is a successful working democracy because the Indian people, since Vedic times, participated in governance—from the village to the state. … It is election season and a time to remember our democratic past. – Dr. Nanditha Krishna

India is a successful working democracy because the Indian people, since Vedic times, participated in governance—from the village to the state. … It is election season and a time to remember our democratic past. – Dr. Nanditha Krishna

If modern India has been a successful democracy, it is because there is an ancient tradition of the idea. Participatory decision-making started in the ancient village councils or panchayats—a testimony to the grassroots democracy that thrived in ancient India. The Rigveda and Atharvaveda refer to the elections of king, prime minister and parliament by the people and some Brahmanas mention kings losing their positions.

The people elected the best person as rajan. The king who failed to protect was deposed. The sabha, samiti and sansad were participatory institutions. The Ramayana and Mahabharata mention the involvement of people in decision-making. Indian texts say that the authority to govern is earned through merit and consensus, not heredity. There are several instances of elected rulers and their committees.

India is a successful working democracy because the Indian people, since Vedic times, participated in governance—from the village to the state. Governments in ancient and medieval India were centralised under a king, but also de-centralised by devolving powers to local bodies and village panchayats in administrative areas in order to safeguard public welfare.

Indian philosophy and polity are based on dharma which, along with artha (material wealth) and kama (desire), is essential for social welfare and happiness. Dharma means the law of righteousness, justice and morality, which sustains and ensures social welfare and progress. Kama and artha, that are contrary to dharma, must be rejected. Sovereignty rests in dharma and the maintenance of this dharma is the work of the sabha (eminent senior citizens) and samiti (popular assembly).

The janapadas were governed by the village headman, while the mahajanapadas were republics or monarchies. The 16 mahajanapadas were known for their rich cultural heritage, military and economic prosperity. Lichchhavi, capital of the Vajji mahajanapada, was ruled collectively by an elected ruler (rajan), deputy ruler (uparajan), general (senapati) and treasurer. The citizens had the right to vote, deliberate and contest for public office. Each post was elected either through consensus or through an election. The sabha would meet and discuss issues. An adult in each family was a member. The public could decide on issues of importance by majority. The final judgement for crime and punishment rested with the elected heads, and records were maintained. Women were equal partners in the labour force, army, agriculture and husbandry.

A detailed description of the democratic system comes from Tamil Nadu. The king had two teams, aimperunkuzhu and enperayam, who were consulted on all matters relating to the state. The village assemblies had substantial powers to govern locally. The roots of the system went back to earlier times, when kingdoms were divided into smaller units. The village, being the smallest unit of administration, had its local self-government known as sabha or gana. The village assemblies were the sabha and the mahasabha, and its members were perumakkal. The members of the assembly looked after temple endowments, irrigation work, tank maintenance and justice. The variyams or sub-committees looked after rural administration, including construction and maintenance of tanks, irrigation channels, land endowments and roads. Particular works were entrusted to groups of committee members, identified with a prefix such eri-variyam, a committee in charge of water bodies.

The 10th century Uttiramerur inscription describes in detail the rules for contesting elections to the variyams. They were selected by lots (kudavolai). They held office for a fixed term and were not eligible for re-election. The sabha fixed the method of appointing members to its variyams. The village was divided into wards (kudumbu) and the members were nominated according to the rules and regulations of the sabha.

The major criterions for contesting the election were age, education, conduct and the requirement that the aspirant should be a taxpayer. The tenure of a committee was for one year and a person who had served could not contest the election again for the next three years. The contestants had to own taxable land and a house. The names of all contestants from the wards were written on palm leaves and put inside a pot. The ‘ballot pot’ was shown to the villagers, after which a young boy took a leaf out of the pot and the name was read out. By this process, committee members from all wards were chosen.

The Manur inscription is also known for its description of local self-government. The committee members of the local bodies consisted of unpaid part-time workers, but there were paid officials who worked full-time. On important occasions, a royal official was present at the meetings of the assembly.

Similarly, the tribes of India have an extremely democratic form of governance. The elders of the tribe form a committee to manage their affairs and choose their leader. The social structure of the tribes ensures equal access to and ownership of natural resources. Many tribes give women prominent and even superior positions.

India also has a tradition of religious democracy or bhakti, which challenged the caste system and was led by saints who helped the masses comprehend philosophical teachings. This is a unique form of democracy by which spiritual development was attainable by common people. Each saint had a favourite god or preferred form of worship and the goal was to finally merge with the divinity.

There are several ancient works of polity, including the Arthashastra and Nitisara, on the science of politics. The Indian Council of Historical Research has a publication, India: Mother of Democracy, which is a mine of information on the country’s democratic traditions. It is election season and a time to remember our democratic past. – The New Indian Express, 5 May 2024

› Prof. Nanditha Krishna is an author, historian, and environmentalist based in Chennai.

Filed under: india | Tagged: hindu dharma, india elections 2024, indian democracy, indian history, indian society | Comments Off on The Indian heritage of democracy – Nanditha Krishna