Hinduism does not sanction caste discrimination. Additionally, the Hindu concept of varna does not trap a person by birth or deter upward mobility. – Vivek Gumaste

Karnataka’s Social and Educational Survey, commonly referred to as the caste census, has stirred up a hornet’s nest and given fresh impetus to the never-ending political discourse about caste in Indian society—a debate that is dominated more by distortions, deliberate misrepresentations, and hyperbole than by truth and accuracy.

Chief Minister Siddaramaiah sermonised: “If there was equality in our Hindu community, then why would anyone convert?”

Bengaluru Archbishop Peter Machado, weighing in on the controversy, stated that “Christianity teaches that all are equal before God. Caste distinctions are not part of our faith.” But that did not stop him from instructing his flock to indicate their caste and sub-caste in the survey in an attempt to garner privileges.

These remarks by the archbishop represent an astounding degree of duplicity. In one breath, you claim that Christianity has no caste distinctions, and in the very next, you encourage Christians to document their original caste so that they can benefit from caste-based affirmative actions that are exclusive to Hinduism and other Vedic religions.

The prevailing misconceptions and deliberate misrepresentations about caste and Hinduism call for clarification and correction.

Caste in Hindu Scriptures

Does the Hindu religion, as per its scriptures, sanction discrimination based on caste? And is caste a function of birth alone and immutable?

The answer to both questions is a resounding no.

The first thing to note is that the word caste is not of Indian origin; it comes from the Portuguese word “casta”, meaning “lineage” or “breed,” which in turn derives from the Latin “castus”, meaning “pure” or “unmixed.” The Portuguese used this term to describe, at best, their limited understanding of the prevailing social order in India. Over the years, caste became synonymous with Hinduism, carrying with it a negative connotation. But whether this word does justice to the traditional social structure of our civilisation is open to question.

Varna is the term used to describe the social structure of the Vedic civilisation according to Hindu scriptures. The word jati (derived from born) also does not figure anywhere in the Bhagavad Gita.

Chapter 18, Verse 41 of the Bhagavad Gita states:

brahmana-kshatriya-visham shudranam cha parantapa

karmani pravibhaktani svabhava-prabhavair gunaih

Translated into English, this literally means: “The duties of the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras are distributed according to their qualities—in accordance with their gunas (and not by birth) and karma.”

A deeper interpretation suggests that all of us have within us varying degrees of these qualities, and the predominance of one or the other is what defines our identities—not birth.

Hindu scriptures do not mandate that birth is the sum total of one’s earthly destiny. In fact, there are instances that clearly negate a rigid association between birth and social upward mobility.

Ved Vyasa is one of the most revered figures in Hinduism—the author of the Mahabharata and the compiler of the Vedic mantras into four distinct texts. One would assume that he was a Brahmin, but he was not. He was an illegitimate child born to Satyavati, the daughter of a poor fisherman.

Similarly, Valmiki, a bandit who repented for his ways, chronicled the Ramayana and came to be venerated as a saint.

Then there is the example of Satyakama from the Chandogya Upanishad. Satyakama was an illegitimate child of a prostitute with no clue to his paternity. But he had a burning desire to learn the scriptures and approached the sage Gautama. When asked about his lineage, Satyakama replied:

“Sir, I do not know what my lineage is. When I asked my mother, she said to me: ‘I was very busy serving many people when I was young, and I had you. As this was the situation, I know nothing about your lineage.’”

Noting his fearless allegiance to truth, sage Gautama responded:

“No non-Brahmin could speak like this. I will initiate you by presenting you with the sacred thread, as you have not deviated from truth.”

Ravana was a Brahmin by birth but a Rakshasa (demon) by his actions—again proving that varna is a fluid mixture of different gunas, with the individual having the option to carve out his own destiny.

So, let us be clear about one thing: Hinduism does not sanction caste discrimination. Additionally, the Hindu concept of varna does not trap a person by birth or deter upward mobility.

Caste in Practice

Having said that, we cannot deny that there is a difference between precept and practice. How do we explain this difference—the horrific caste practices that we see in daily life?

Humans have, over the ages, distorted religious edicts to serve their own selfish interests, creating in the process an unequal society. Caste today is a corruption of the society we live in, not a derivative of the Hindu religion per se.

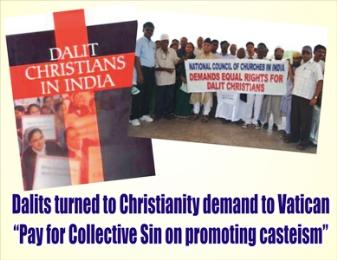

This is why caste discrimination persists despite conversion to Christianity or Islam. Dalits who convert to Christianity continue to be discriminated against; they are forced to attend separate Dalit churches and bury their dead in separate burial grounds. Some Christians do not hesitate to flaunt their Brahmin heritage. Syrian Christian families in Kerala routinely have gatherings to emphasize their upper-caste origin. Syrian Christians—one of the world’s oldest Christian communities—believe they are descendants of high-caste Brahmin families converted to Christianity by St. Thomas in the 1st century CE.

Even Farooq Abdullah, the Muslim leader of the National Conference, frequently refers to his Kashmiri Pandit Brahmin origin.

Religious conversion has not resolved the problem of caste, as claimed by the Abrahamic religions, as is evident from the persistence of caste among converted Christians and Muslims. Caste was an expedient tool that was craftily exploited by predatory non-Hindu religions to defame Hinduism, create confusion among Hindus, and deceptively lure them away to other faiths.

This Vedic concept of varna was erroneously interpreted by less advanced foreigners and inadequately translated into an alien, less developed language, giving it a faulty definition. Colonial hegemony and the dominant status of the English language cemented this warped definition into our psyche—so much so that even Hindus have come to accept it as gospel truth.

Ignorance about Hindu scriptures deters us from stridently confronting these untruths and even makes us apologetic about our own religion. This has to change. Hindus need to confront these untruths boldly and confidently.

Other religions too have an unsavoury past. Devout Christians in America captured millions of Africans, transported them in chains across the Atlantic Ocean, and forced them to work in cotton fields like animals. Spaniards slaughtered the Aztecs in South America by the thousands in the name of religion. The thousand-year-long genocide of Hindus in India by Muslim rulers is all too well known—again, all in the name of religion. But do we affix criminality to these religions?

This selective targeting of Hinduism for the ills of the past is skullduggery at its worst and unacceptable.

Dalits During Muslim and Christian Rule

An examination of the history of caste in the subcontinent over the last two millennia sheds further light on the attitude of non-Hindu religions toward caste and is a big eye-opener. For over a thousand years, political power in the subcontinent lay in the hands of non-Hindus—Muslims for approximately 1,000 years and Christian Britain for 200 years.

Unfortunately, during this period there was not a single government initiative aimed at uplifting the Dalits or eradicating caste practices. Surprisingly, even under Buddhism—which held sway over India for more than 500 years until Hindu revival in the 8th century—we do not see notable examples of Dalit upliftment.

My direct and blunt query to one and all is this: during this long period of Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist rule, why was there no serious attempt to eradicate casteism or allay the sufferings of the Dalits?

This was because caste among Hindus, as perceived by these other religions, was a deficiency to be highlighted—not to better the conditions of the downtrodden but to serve their own vested interests of conversion. So, when these religions shed crocodile tears over the plight of Dalits, I take it not with a pinch but with a ton of salt.

Government and Reservations

The only real attempt to uplift Dalits came after 1947, when a predominantly Hindu government came to power in Delhi. India boasts one of the most ambitious and extensive affirmative action plans the world has ever seen: the reservation programme for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

This was implemented through introspection and self-realisation. The Dalits in India did not have to wage a violent struggle or a civil disobedience movement like Blacks in America to achieve their rights. This must be noted by all—including Dalits — not as gratitude but as intellectual acknowledgment.

Hinduism, like other religions, has its deficiencies. But it is one religion that has the courage and will to accept and rectify the infirmities within its midst. Hinduism has acknowledged the horrors of caste practice and has made, and continues to make, amends. I do admit much more needs to be done.

Therefore, to deliberately overlook the great strides made post-Independence is nothing but deliberate obfuscation. Despite some inconsistencies, Hinduism is arguably the most tolerant, compassionate, and open religion — with few parallels in the world. Let us not allow people to confuse us into believing otherwise. – News18, 10 October 2025

› Vivek Gumaste is an academic and political commentator based in the USA.

See also

- St. Thomas and Caste – Ishwar Sharan

- Syrian Orthodox bishop doubts St. Thomas visited South India – Times News Network

- The question of the St. Thomas origin of Indian Christianity – C.I. Issac

- Jacobite Syrian bishop demolishes Kerala’s conversion myth – Thufail P.T.

- Caste system deep-rooted among Christians in India – T.A. Ameerudheen

Filed under: india, world | Tagged: caste, caste in christianity, indian society, jati, varna ashram | Comments Off on Caste discrimination not sanctioned by Hindu scriptures – Vivek Gumaste