“That Vande Mataram should ever have been challenged on the ground that it was too Hindu and not secular enough for a country where there were millions of Muslims, is a sad symptom of national decadence.” – K.D. Sethna

Prime Minister Narendra Modi must be congratulated for making the 150th anniversary of ‘Vande Mataram’, the song that stirred the soul of a fallen nation, into a State celebration. For what is a State—any State—which has no statement to make? Respect, even reverence, for one’s motherland is the least, some would even say the utmost, Indian statement.

For Ma Bharati is not just a country, a political union, a nation, or even a state of mind. She is nothing short of a force of consciousness. In invoking her, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, unified and activated the dormant soul of a defeated people, so enwrapped in darkness that it needed nothing less than a new mantra, almost magical in its incantatory power, to agitate it into awakening.

If I sound so enthusiastic, even laudatory to the point of being reverential, it is because I have just re-read and inwardly recited Bankim’s poem, India’s national song. Yes, it was so affirmed by India’s Constituent Assembly in 1950, the same body that gave us our Constitution. Let me confess that I have never sung or listened to ‘Vande Mataram’ without being deeply moved, even to tears. And today is no exception.

But here’s a slight problem. The full song, for various political and historical reasons, is not easily available, especially in Devanagari. I actually had to source the full original from sanskritdocuments.org. This leads me to offer an aside to the powers that be. In our efforts to promote our many national languages, in addition to the two official ones, namely Hindi and English, we must try to make important texts available not only in translation, but in transliteration. That is, from Punjab to Kerala, Gujarat to Assam, original texts should be in both Devanagari and Roman transliteration so that we can try to read them in original.

When it comes to ‘Vande Mataram’, most educated Indians will find it easy to grasp, its mixture of Sanskrit and Bangla heavily weighted in favour of the former, rendering it truly a national text in much of the country. Which leads me to some slightly more chauvinistic Bengali friends, mostly Hindus. They are quick to point out that Bankim spoke of seven crore voices (saptakoti kantha), slightly in excess of the population of Bengal Presidency in his time. The teeming masses of undivided India, even in the late 19th century, numbered some 285 million souls. Ergo, they argue, Bande (with a b), not Vande (with a v) Mataram, was for Bengalis, not Indians.

Thank you, but why be so literal, I ask. Why can’t Bengal stand for India? After all, most important ideas in the colonial period, including Hindutva, coined before V.D. Savarkar by Chandranath Bose, came from Bengal. What Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow, they used to say. Why should it be the other way round today—what India thinks today, Bengal thinks tomorrow? If we cry for national unity, even Hindu unity, why should Hindu Bengalis carp and cavil so much?

My apologies if I offend anyone. Given how much a Bongophile I am, my Kolkata friends long ago, albeit grudgingly, called me an ‘honorary Bengali’. I found that one of the most honourable, in addition to flattering, compliment I have ever received.

From the regional to the ‘secularist’ national objection. I think it was K.D. Sethna, better known as Amal Kiran in Aurobindonian circles, who answered it best and most politely: “That Vande Mataram should ever have been challenged on the ground that it was too Hindu and not secular enough for a country where there were millions of Muslims, is a sad symptom of national decadence. Perhaps a still sadder one is the lukewarm apologia put up for it at times—namely, that the goddess invoked should not worry anybody since nobody now believes in the reality of such a being and she can be taken as a harmless poetic metaphor for the motherland. Heaven save us from this kind of secularism!”

It was indeed Aurobindo who not only hailed Bankim as a ‘rishi’ but Vande Mataram as a mantra: “Among the rishis of the later age we have at last realised that we must include the name of the man who gave us the reviving mantra which is creating a new India, the mantra Bande Mataram.” In an article reproduced in The Standard Bearer in 1920, Aurobindo even went so far as to say, “A greater mantra than Bande Mataram has to come.”

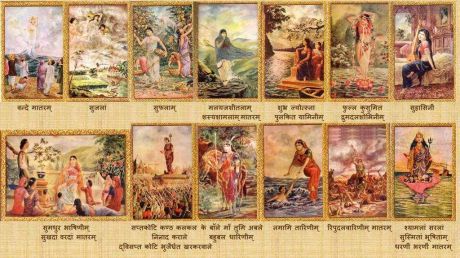

I think that is because Bankim hails Mother India as a combination of Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati—the three powers we need at the practical and psychic levels—to turn earthly existence into a successful and cooperative enterprise. Understood in this light, there is nothing parochial, narrowly religious, or even rigidly nationalistic about Vande Mataram.

Rather, especially when understood as a mantra, it signifies the energising feminine or active force in any transformative endeavour, whether physical, vital, intellectual, psychic, or spiritual. Writing on Bande Mataram, Aurobindo explained that a nation, like an individual, has three bodies—the physical (annamaya kosha), the vital energy of its citizens (pranamaya kosha), and, “Within the gross body is a subtler body, the thoughts, the literature, the philosophy, the mental and emotional activities, the sum of hopes, pleasures, aspirations, fulfilments, the civilisation and culture, which make up the sukshma sharir of the nation … but within them all is the source of her life, immortal and unchanging, of which every nation is merely one manifestation, the universal Narayan, One in the many of whom we are all the children.”

The symbolism is Hindu, but the meaning transcends all boundaries. So it should be with Vande Mataram. Bankim’s mantra still holds good, unfolding its meaning gradually, like a time-release capsule. In it, not just a nation regains its long-lost Mother, but the Mother herself finds her long-lost children.

That is why, apart from any official reason, let us really try to read, recite, and understand this mantra. – The New Indian Express, 10 November 2023

Filed under: india | Tagged: bankim chandra chattopadhyay, hindu civilisation, hindutva, national song, vande mataram | Comments Off on Vande Mataram: A mantra to stir the nation’s soul – Makarand R. Paranjape