Why do so many Indians revere Dalrymple’s distorted narratives? It’s a relic of colonial conditioning, where foreign acknowledgement is perceived as more credible or prestigious than self-validation. Dalrymple’s ability to package India’s past in a format palatable to Western audiences becomes a selling point for Indian readers, who see in his works a historical account and an endorsement from the global intellectual elite. – K. Yatish Rajawat

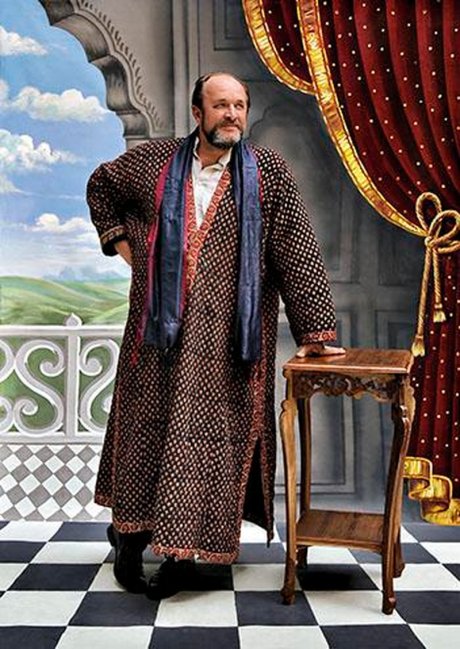

William Dalrymple’s The Golden Road exemplifies the paradox of Indian admiration for colonial-era narratives that distort, downplay, or outright erase the grandeur of India’s achievements. A gifted narrator and researcher, Dalrymple’s oeuvre often serves as a subtle affirmation of the “White man’s gaze,” which many Indians paradoxically lap up as validation. But what is being validated here, and why does this external endorsement appeal to so many? What does this say about our understanding of our history?

At the heart of the issue is Dalrymple’s treatment of India’s history—partial, selective, and skewed toward perpetuating colonial myths that prioritise Buddhist achievements and Islamic influences while strategically downplaying or excluding the towering contributions of Hindu dynasties like the Guptas and the Palas. While dazzlingly written, his narrative misrepresents India’s past by failing to give due credit to the Hindu emperors and intellectual ecosystems that powered many of the achievements he celebrates. Of course, he can get away with it because he does not claim it is a historically accurate reflection of all the facts. However, in a world where very few people read books, the masses make up their opinions of books from podcasts, reviews, and YouTube shorts, and the popular narrative is the new factual history.

Dalrymple’s early books, such as City of Djinns (1993) and White Mughals (2002), focused on India as an exotic landscape seen through the prism of its encounters with the West. These works romanticised colonial-era interactions, often portraying India as a passive recipient of external influences—Persian, Mughal, or British. While important, his fascination with the syncretic elements of India’s past tended to obscure the vibrant, self-sustaining core of India’s Hindu traditions and their immense contributions to global civilization.

With The Last Mughal (2006), Dalrymple shifted his focus to the fall of the Mughal Empire, casting Bahadur Shah Zafar as a tragic figure emblematic of a multicultural India destroyed by colonialism. This marked a subtle broadening of his narrative but still centred around periods of foreign rule, framing Indian identity through the lens of invasions, adaptations, and losses rather than Indigenous creativity and agency.

In The Golden Road (2023), Dalrymple takes a more expansive view, acknowledging India’s pivotal role in shaping global civilization. He details the diffusion of Indian knowledge—mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and metaphysics—across Central Asia, China, and Europe. However, even this work reveals his long-standing reluctance to credit Hindu dynasties, such as the Guptas or Palas, with creating the intellectual and material infrastructure that enabled these achievements. By emphasising Buddhist or Islamic conduits of Indian knowledge, Dalrymple perpetuates a narrative that sidelines Hindu contributions and their resurgence in contemporary discourse.

Dalrymple’s evolving view mirrors the shifting dynamics of India’s self-perception. Over the last decade, thanks to Indian authors such as Sanjeev Sanyal and Vikram Sampath, there has been a marked resurgence of Indian identity, driven by a reassertion of pride in the country’s indigenous achievements. From a post-Independence generation that often internalised colonial narratives to a modern India that celebrates its civilisational ethos, the government has begun reclaiming its history with renewed confidence.

This resurgence has forced even Western historians like Dalrymple to engage with India’s ancient knowledge systems and their global influence. The increased interest in India’s role in mathematics, medicine, and metaphysics—fields long overshadowed by Eurocentric historiography—reflects a growing recognition of India as not just a receiver of knowledge but a global innovator. Dalrymple’s acknowledgement of India’s contributions to the Abbasid Caliphate, the Tang dynasty, and even the European Renaissance signals a partial shift in his narrative, albeit one still constrained by his “outsider’s gaze”.

The pressure to remain relevant and be read might explain why Dalrymple expands his focus in The Golden Road to include India’s knowledge systems. However, he still frames much of it through external validation (e.g., via Chinese, Arab, or European conduits). He has expanded his range of influences and moved away from the leftist view of Indian history but created his nuance, which may sit well with his Western readers.

Take, for instance, Dalrymple’s treatment of the Guptas. This dynasty presided over India’s Golden Age, during which advancements in mathematics, astronomy, literature, and governance laid the foundation for global scientific progress. Yet, Dalrymple skips Faxian’s vivid accounts of the Gupta era’s welfare state, thriving intellectual hubs, and moral society. He recounts Aryabhata’s brilliance and Brahmagupta’s ground-breaking work but disconnects them from the emperors and the meticulously cultivated ecosystem that enabled such accomplishments. The omission of Samudragupta and Skandagupta—arguably among the greatest empire-builders in world history—is emblematic of a broader reluctance to glorify Hindu leadership in global narratives.

Similarly, his brief nod to the Palas—the torchbearers of Indian learning post-Gupta—ignores their pivotal role in founding institutions like Vikramshila and Somapura, which preserved and disseminated India’s knowledge across Asia. The symbiotic relationship between Buddhist and Hindu scholars, the unifying spiritual ethos, and the Palas’ patronage of Sanskrit learning go underexplored in favour of Tang dynasty anecdotes and Buddhist emissaries.

Dalrymple’s selective focus aligns with a broader trend of viewing Indian history through a colonial lens—one that amplifies the influence of external actors while relegating India’s Indigenous forces to the background. This explains his overemphasis on Chinese, Tibetan, and Islamic conduits of Indian knowledge while underplaying the original Indian frameworks that generated and sustained such knowledge. For example, his treatment of the Barmakid viziers focuses on their Abbasid context, ignoring their roots in the Sanskrit intellectual traditions of Balkh and Ujjain.

Why, then, do so many Indians revere these distorted narratives? It’s a relic of colonial conditioning, where foreign acknowledgement is perceived as more credible or prestigious than self-validation. Dalrymple’s ability to package India’s past in a format palatable to Western audiences becomes a selling point for Indian readers, who see in his works a historical account and an endorsement from the global intellectual elite.

The problem lies in the subtle erasure of self-hood. By outsourcing the validation of India’s achievements to external voices, we undermine our scholarly traditions and the historical agency of our ancestors. Dalrymple’s narrative, while compelling, inadvertently reinforces the idea that India’s greatness needed external validation—be they Chinese monks, Arab scholars, or European traders—to shine. For a civilisation, it is challenging and a sad commentary on our society’s ability to have its own identity without seeking validation from outsiders. This validation does not limit itself to historical fiction and pours into many other narratives, affecting our voices. Our voices are indignant about the world that does not acknowledge our past glories. It need not be angry. It can be calm and talk about our ability to influence a Bharatiya future for the world.

They should be reflecting and celebrating our current status and not using the past only to build our global cultural narrative. Confidence in the current and the ability to build our own future as a nation are more crucial in shaping our narrative than depending upon the glorious heritage of only the past to establish the identity of the nation.

This is not merely an academic issue but a narrative challenge. Can a nation tell its story only from its cultural and intellectual moorings of the past, or does it need to present here and now our achievement? It is not an either-or argument. It is a sum of both, and its nuance lies in its presentation. Hence, the ideas of many Bharat have many things but should be focused on something other than Western interpretations. Instead, the Western world should believe in the future of Bharat. In a way, Dalrymple’s shift indicates that it has begun. – News18, 8 Decemeber 2024

› K. Yatish Rajawat is a public policy researcher who works at the Gurgaon-based think and do tank Centre for Innovation in Public Policy (CIPP).

See also

- The Dalrymple massage of the St. Thomas myth – Koenraad Elst

- William Dalrymple: Admiring Indian civilisation, undermining the Hindu spirit behind it – Utpal Kumar

Filed under: india, UK | Tagged: academic hinduphobia, hindu civilisation, hindutva, syndicated hinduism, william dalrymple |