We must realise that Dharma is greater and more profound than any sampradaya—and there are hundreds of them—through which Dharma chooses to manifest. – Aravindan Neelakandan

We must realise that Dharma is greater and more profound than any sampradaya—and there are hundreds of them—through which Dharma chooses to manifest. – Aravindan Neelakandan

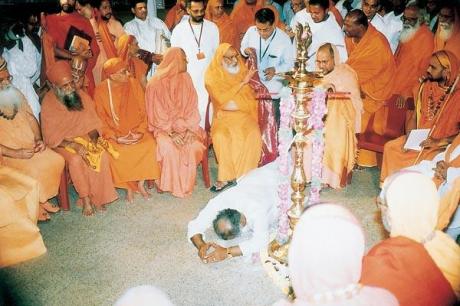

In recent years there has been a great deal of churn within the Hindu society regarding taking back control of Hindu religious institutions. In discussions on such topics many feel the need to find a Hindu equivalent of a pope, a pan-Hindu figure as a religious head.

In trying to find a Hindu equivalent for a pope or religious head, references are often made to the four Shankaracharyas. Many activists who feel strongly for Hindu causes, sometimes with justification and sometimes without, do make the case for according a special status to the great Shankaracharyas.

“Did you create a committee headed by the Shankaracharyas for the Kashi corridor?”

“Did you send an invitation and offer a place of honour for the Shankaracharyas for the bhoomi pooja at Ayodhya?”

“Have you consulted the Shankaracharyas for the date of the launch of next Chandrayan mission?”

Do not get me wrong. I have great respect for the peethams of the Shankaracharyas, attributed to the genius of Adi Shankara Bhagavatpada. I know that many of the devotees of the Shankaracharyas hold them as authorities in all domains of life. Adi Shankara should be regarded as one of the greatest propounders of the Ekanmavada version of Advaita; indeed, for most of us today, the Ekanmavada version of Advaita is Advaita.

But the problem is that the very small number of Shankaracharyas we have today are not representative of the diversity of religious orders and traditions among Hindus.

Hindu Dharma is far larger and far more diverse and richer than the order of the four peethams of Shankaracharyas, however great and exalted they are. Even among the four peethams—plus one—there are discrepancies about the place where their founder attained samadhi and his historical period and whether or not he established a particular matha. Then there are other sampradayas.

Just as how the reformist—radical, genuine or pretentious—is wrong in asking the rhetorical question “can a Dalit become a Shankaracharya?”, equally wrong are the people who want ex-cathedra statements from the Shankaracharyas as guiding principles for each and every step the government takes.

There are many sampradayas. There are those who lay their emphasis on the Smritis, and there are those who, while not condoning or condemning the Smritis, have more respect for the Agamas. There are dualists and qualified non-dualists. There are Shaivaites, some of whom have, and wrongly so, an aversion for Smarthas.

There are Smarta attempts at grandstanding at the expense of Shaivas, like the famous story of Shiva himself affirming the validity of Sankara’s version of Advaita to the Siddhantins at one of the latter’s most sacred places—Thiruvavadhuthurai.

So, attempts to posit one sampradaya as the be-all and end-all of Hindu Dharma, however exalted and dominant that sampradaya may be, can result in bitter fissures in Hindu unity that has been building up with all kinds of hindrances in post-independent India.

Then there is the recent historical baggage.

The Shankaracharyas, true to their adherence to the Smritis, supported some bizarre status-quo conditions as against the reformist movement that the Hindutvaites initiated. Had the society adhered to the stands of the Acharyas, we would have had today legal child marriages, no schools or colleges for women, no women working in any field except being housewives, no entry of Scheduled Communities into temples, etc. Arya Samajists would not even have been recognised as Hindus had certain Shankaracharyas of the time had their way.

To the credit of the venerable Shankaracharyas, while they adhered to their principles, they did not start a massive counter-movement against these reforms. Some of the greatest reformers were also some of the greatest devotees of the Shankaracharyas of the period. That they did not agree on even a very important issue, such as the age limit for marriage for women, did not make the gurus excommunicate the disciples; though the disciples who adhered to orthodoxy and those who stood for reforms did have a bitter exchange of words.

Hence to treat the heads of some select sampradayas as popes for the entire Hindu society is against the interest of the Hindu society at large and can have disastrous consequences for Dharma and society.

A case in point is Tamil Nadu.

Here Swami Chidbavananda single-handedly revived Dharma as a spiritual preceptor, educationist, author and institution builder at a time when Dravidianism was at it zenith. While his legacy today is marked by his commentaries on the Bhagavada Gita and Thiruvasagam, what is not much known outside a small circle is that he had authored a large number of plays based on the Puranas and Ithihasas, for children.

Equally important is the contribution of Thirumuruga Kripananda Variyar Swamigal. He could provide profound messages to both the child and the pandit in the same katha-kalaksheba he made. He also wrote for children and adults, treating both with respect and communicated with them in all sincerity. Paramacharyas of Dharumapuram Adheenam, too, stood steadfast in fighting against the missionary manoeuvres to digest Vedic Shaivism and even use the fraudulent distortions as evangelical tools.

Consider the pitfalls of projecting the pontiff of one particular matha as the representative or guru of the Hindu fold. There are at least a dozen other large mathas—some of them older than the mathas often taken to be representative of the Hindu fold.

There are Shaivite, Sri Vaishnavite, and Smartha institutions—each performing yeoman service. How do we choose one as the sole representative? A large number of temples, schools, hospitals and other institutions are administered by these mathas.

How does one ignore the contributions and religious importance of a matha like the Parakala Matha? Founded in 13th century, with an unbroken lineage for centuries, the matha surely can’t be forgotten in our quest to enthrone a pope of some sort?

Do remember that these are examples from just one state of India. Should we account for all the states, all the new institutions such as the Ramakrishna Mission and the recent global expansion of the Hindu fold, we will be left gasping for breath just counting the number of religious orders and leaders.

We must realise that Dharma is greater and more profound than any single sampradaya,—and there are hundreds of them—through which Dharma chooses to manifest.

But who runs the temples then? Our challenge is to devise new institutions where ancient mathas and Hindu society can come together. These could be spaces where new energy and ideas are catalysed, where temples transform into centres of Hindu cultural life like they once where. This will also see an impetus for change—something that we must all learn to welcome. – Swarajya, 5 July 2021

› Aravindan Neelakandan is an author and cultural commentator with a master’s degree in psychology and economics. He is a contributing editor at Swarajya.

Filed under: india, world | Tagged: hindu acharyas, hindu religious leaders, hinduism, sanatana dharma, shankaracharyas |