“The Aurobindo that interests me is the one who turned from a life of hectic action to a life of contemplation, but was able, during his forty-year retirement, to write a shelf full of books on philosophy, political theory, and textual criticism, along with thousands of letters and, yes, that epic in iambic pentameter, Savitri.” – Peter Heehs

“The Aurobindo that interests me is the one who turned from a life of hectic action to a life of contemplation, but was able, during his forty-year retirement, to write a shelf full of books on philosophy, political theory, and textual criticism, along with thousands of letters and, yes, that epic in iambic pentameter, Savitri.” – Peter Heehs

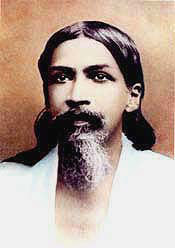

How do you write about a man who is known to some as a politician, to others as a poet and critic, to still others as a philosopher, and to a not inconsiderable number as an incarnation of God? This is one of the problems a biographer of Sri Aurobindo (Aurobindo Ghose, 1872-1950) has to face. Known in the West mostly to specialized audiences (people interested in South Asian history, literature, philosophy, and spirituality), Aurobindo is renowned in his native India as one of the most outstanding, and most many-sided men of the twentieth century. This has not prevented his legacy from being bitterly disputed.

How do you write about a man who is known to some as a politician, to others as a poet and critic, to still others as a philosopher, and to a not inconsiderable number as an incarnation of God? This is one of the problems a biographer of Sri Aurobindo (Aurobindo Ghose, 1872-1950) has to face. Known in the West mostly to specialized audiences (people interested in South Asian history, literature, philosophy, and spirituality), Aurobindo is renowned in his native India as one of the most outstanding, and most many-sided men of the twentieth century. This has not prevented his legacy from being bitterly disputed.

Some historians and politicians see him as one of the forerunners of Mahatma Gandhi, others as a precursor of today’s aggressive Hindu nationalists. Admirers of his writings see his epic in iambic pentameter as the harbinger of a new kind of poetry, but most contemporary poets and critics dismiss it as a throwback to the Victorian era. The opinions of amateur and professional philosophers are polarized along the same lines. There is general agreement among students of religion that Aurobindo was a remarkable mystic, but few are willing to swallow the claim of some of his followers that he was an avatar, like Krishna, Chaitanya or Christ.

In The Lives of Sri Aurobindo I made Aurobindo’s many-sidedness the foundation of the structure of the book. Each of the five parts deals with one of his “lives”: the family man, the scholar, the revolutionary, the yogi and philosopher, and the spiritual guide. The first three go together pretty well, since the conventions of literary and political biography are similar. The writer is expected to present the significant events of a notable life in a chronological narrative, supporting the story with a scholarly apparatus based on primary sources. It was easy for me to do this when I wrote about Aurobindo’s life in politics. Discussing his role at the Surat Congress of 1907, for example, I was able to draw on government files, police reports, newspaper stories, Aurobindo’s reminiscences, and the reminiscences of others in English, Bengali, and Gujarati. But what was I to do with the information that a few days after the Congress, Aurobindo sat with a guru who taught him a meditation technique, and that, as Aurobindo later put it, “In three days – really in one, my mind became full of an eternal silence” – by which he meant the mental stillness and freedom from ego known as Nirvana.

In The Lives of Sri Aurobindo I made Aurobindo’s many-sidedness the foundation of the structure of the book. Each of the five parts deals with one of his “lives”: the family man, the scholar, the revolutionary, the yogi and philosopher, and the spiritual guide. The first three go together pretty well, since the conventions of literary and political biography are similar. The writer is expected to present the significant events of a notable life in a chronological narrative, supporting the story with a scholarly apparatus based on primary sources. It was easy for me to do this when I wrote about Aurobindo’s life in politics. Discussing his role at the Surat Congress of 1907, for example, I was able to draw on government files, police reports, newspaper stories, Aurobindo’s reminiscences, and the reminiscences of others in English, Bengali, and Gujarati. But what was I to do with the information that a few days after the Congress, Aurobindo sat with a guru who taught him a meditation technique, and that, as Aurobindo later put it, “In three days – really in one, my mind became full of an eternal silence” – by which he meant the mental stillness and freedom from ego known as Nirvana.

It certainly is legitimate to cite Aurobindo’s own statements about this and other inner experiences. But personal reminiscences don’t count for much in scholarly biographies unless they are backed up by objective data and analysis. But what sort of objective data was I to look for? (Nobody knew what was going on in Aurobindo’s head.) If I wanted to discuss this inner event, did I have to switch (in mid stream) from the conventions of scholarly biography to the conventions of spiritual biography, that is, hagiography? Or could I get beyond the conventions of both genres?

Hagiography in its original sense, writing about the lives of saints, has been practiced since the first century CE (the Gospels, the Buddhacarita). What distinguishes the hagiographic from the critical approach is not that hagiographers are sympathetic to their subjects, but that they base their accounts on unverifiable assumptions that are likely to be accepted only by members of the discursive community that they belong to. Few modern non-Catholic readers are likely to take seriously the claims of Angelo Pastrovicchi that Joseph of Cupertino could fly. On the other hand, Pastrovicchi’s eighteenth-century work remains a vital source for any anyone wishing to write about the Italian saint. A scholar may reject levitation as inconsistent with what we know about gravity but still accept that Joseph had visions, as Pastrovicchi claims.

Hagiography in its original sense, writing about the lives of saints, has been practiced since the first century CE (the Gospels, the Buddhacarita). What distinguishes the hagiographic from the critical approach is not that hagiographers are sympathetic to their subjects, but that they base their accounts on unverifiable assumptions that are likely to be accepted only by members of the discursive community that they belong to. Few modern non-Catholic readers are likely to take seriously the claims of Angelo Pastrovicchi that Joseph of Cupertino could fly. On the other hand, Pastrovicchi’s eighteenth-century work remains a vital source for any anyone wishing to write about the Italian saint. A scholar may reject levitation as inconsistent with what we know about gravity but still accept that Joseph had visions, as Pastrovicchi claims.

Aurobindo spent the last forty years of his life immersed in the practice of yoga. He wrote about his yogic experiences in a diary, the Record of Yoga, and in letters to his followers. Are these the sort of sources that a scholarly biographer can cite? It certainly would be uncritical to accept at face value all that Aurobindo wrote about his inner life; but it would be a different sort of negligence to refuse to consider accounts of inner experience a priori grounds, or to explain them away according to the assumptions of one or another social-scientific orthodoxy.

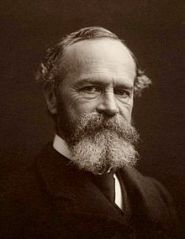

I think that William James had the right approach to this sort of material. “One cannot criticize the vision of a mystic,” he wrote in A Pluralistic Mystic, “one can but pass it by, or else accept it as having some amount of evidential weight.” I couldn’t simply close my eyes to Aurobindo’s accounts of his mystical experiences, so I accepted them as evidence of a vivid, if sometimes enigmatic inner life. I wonder however whether James got it right when he said we “cannot criticize the vision of a mystic.” Many spiritual traditions – the Catholic Christian and Tibetan Buddhist, for example – recognize a distinction between true and misleading visions. I don’t have the necessary discernment to criticize Aurobindo’s visions as visions; but I recognize – as Aurobindo himself did – that inner visions and experiences are open to different interpretations.

I think that William James had the right approach to this sort of material. “One cannot criticize the vision of a mystic,” he wrote in A Pluralistic Mystic, “one can but pass it by, or else accept it as having some amount of evidential weight.” I couldn’t simply close my eyes to Aurobindo’s accounts of his mystical experiences, so I accepted them as evidence of a vivid, if sometimes enigmatic inner life. I wonder however whether James got it right when he said we “cannot criticize the vision of a mystic.” Many spiritual traditions – the Catholic Christian and Tibetan Buddhist, for example – recognize a distinction between true and misleading visions. I don’t have the necessary discernment to criticize Aurobindo’s visions as visions; but I recognize – as Aurobindo himself did – that inner visions and experiences are open to different interpretations.

What about the assertion that Aurobindo was an avatar? I can’t say that the question interests me very much. Aurobindo never claimed the distinction for himself, and I don’t think anyone alive is in a position to say one way or the other. The Aurobindo that interests me is the one who turned from a life of hectic action to a life of contemplation, but was able, during his forty-year retirement, to write a shelf full of books on philosophy, political theory, and textual criticism, along with thousands of letters and, yes, that epic in iambic pentameter. People will continue to differ about the significance of his work, but its very mass is there for all to see. His life as a yogi and spiritual leader is more difficult to quantify, but it certainly will not be forgotten soon. I tried to do justice to all sides of this versatile man, but to do so I had to be unconventional in more ways than one. – CUP Blog, 4 August 2008

What about the assertion that Aurobindo was an avatar? I can’t say that the question interests me very much. Aurobindo never claimed the distinction for himself, and I don’t think anyone alive is in a position to say one way or the other. The Aurobindo that interests me is the one who turned from a life of hectic action to a life of contemplation, but was able, during his forty-year retirement, to write a shelf full of books on philosophy, political theory, and textual criticism, along with thousands of letters and, yes, that epic in iambic pentameter. People will continue to differ about the significance of his work, but its very mass is there for all to see. His life as a yogi and spiritual leader is more difficult to quantify, but it certainly will not be forgotten soon. I tried to do justice to all sides of this versatile man, but to do so I had to be unconventional in more ways than one. – CUP Blog, 4 August 2008

Filed under: india | Tagged: biography, censorship, controversy, freedom of expression, hagiography, peter heehs, politics, scholarship, sri aurobindo, sri aurobindo ashram, the mother, yoga |

we never go into the details of origin of a river or a sanyaasi. a great saint of tamils said if you believe in god he is if not he is not.

LikeLike

Thank you for the link. We have reposted Claude Arpi’s article with a new title Heehs’ Heresy: Sri Aurobindo would have been amused.

Hopefully the Home Minister will apply his mind and revoke the Quit India notice issued to Heehs.

Obviously this controversy is more about internal ashram politics than Heehs’ book. The Odisha group have never been happy with the ashram management. That they would induct the CPI(ML) into their demonstrations doesn’t speak very well of them.

LikeLike

http://www.rediff.com/news/special/controversy-over-book-would-have-amused-sri-aurobindo/20120410.htm

“Sometimes, I have the feeling that Sri Aurobindo is smiling at the controversy and waiting for India to look and walk into her future.” – Claude Arpi

LikeLike

Yes, Madhusudana was the creator of the Dashanami Naga Akharas who at one time policed the Dashanami sannyasis and protected them from Muslim attacks.

Unfortunately the Naga order has declined and as a result we have the likes of Sex Swami Nithyananda parading around the countryside. Had Nithyananda lived a hundred years ago, the Nagas would have given him “jal samadhi” and been done with him.

LikeLike

Bengal has produced great souls, but many of them are referred after Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the reformist leader.. Even though Chaitanya Mahaprabhu started the bhakti movement centuries back, there was one great saint called Madhusudhan Saraswathi. Many serious Sanatanis consider him as the best Bengal has produced in terms of Bairagya and scholarly intuition. His commentaries are numerous and his commentary on Gita is very good.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madhus%C5%ABdana_Sarasvat%C4%AB

It is said: (Only) the Goddess of Learning, Sarasvati knows the limits of (knowledge of) Madhusūdana Sarasvati. And Madhusūdana Sarasvati knows the limits of (knowledge of) Goddess Sarasvati.

LikeLike

Yes, Swamiji, I have read somewhere, may be in the biography written by Romain Rolland that Vivekananda was a beef-eater. Ever since I have lost all my respect and admiration for Vivekananda. A realized Hindu can never be a beef-eater. The argument that a sannyasin is not bound by any social norm is an idiotic one. A sannyasi has no right to mislead the masses. Besides, Vivekananda was blinded by the material glitz of the west and thought that industrialization pursued in the west was the only panacea for India’s all ills. That is the only reason why he failed to fathom the significance – both material and spiritual – of cow. With such a view there is no wonder that Ramakrishna Mission has turned out to be an anti-Hindu Organization.

LikeLike

Excerpted from Ban the Ban: India bans books with a depressing frequency | Ramachandra Guha | The Telegraph, Calcutta, 30 July 2011

A ban makes news; the withdrawal of a ban does not. Gandhi scholars in particular, and Indians in general, owe Rajmohan and Gopalkrishna a debt of gratitude, for pressurizing the government to allow the free circulation of Joseph Lelyveld’s The Great Soul in 27 states of the country. It remains illegal to own or possess a copy of the book in the 28th state of the Union, which happens to be Gandhi’s own. By banning the book before it was available, Modi thought he could camouflage his sectarian leanings in the protective cloak of the Mahatma’s pluralism. In the event, once the government of India — bowing to the sensible advice of Gandhi’s grandsons — allowed the free circulation of the book, the fact that it is not yet legally available in Gujarat only exposes the insularity and xenophobia of that state’s chief minister.

Sadly, the bravery (and decency) of Gandhi’s grandsons has not been emulated by defenders or descendants of some other great men of modern India. Consider the fate, within India, of a biography of Sri Aurobindo written by Peter Heehs. Heehs is a real scholar, the author of several substantial works of history (among them The Bomb in Bengal). What’s more, he was for many years in charge of the archives in the Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry.

In 2008, Columbia University Press in New York published Peter Heehs’s The Lives of Sri Aurobindo. The product of a lifetime of scholarship, its empirical depth and analytical sharpness is unlikely to be surpassed. For Heehs knows the documentary evidence on and around Aurobindo’s life better than anyone else. He has a deep knowledge of the political and spiritual worlds in which his subject moved and by which he was shaped.

Alas, this remarkable life of a remarkable Indian cannot be read in India. This is because of an injunction on its sale asked for by self-professed devotees of Aurobindo, and granted by a hyper-active high court in Orissa. Heehs’s book is respectful but not reverential. He salutes Aurobindo for his contributions to the freedom struggle. Before Aurobindo, writes Heehs, “no one dared to speak openly of independence; twenty years later, it became the movement’s accepted goal”. He praises Aurobindo’s contributions to literature and philosophy. However, Heehs is gently sceptical of the claim that Aurobindo possessed supernatural powers. “To accept Sri Aurobindo as an avatar is necessarily a matter of faith,” he writes, adding that “matters of faith quickly become matters of dogma”.

This understated, unexceptionable statement drove the dogmatic followers of Aurobindo bananas. Some devotees filed a case in the Orissa High Court, restraining the Indian publisher from circulating the book in India. Other devotees filed a case in a Tamil Nadu court, seeking the revocation of Peter Heehs’s visa and his extradition from this country. By these (and other) acts, the contemporary keepers of Aurobindo’s flame showed themselves to be far less courageous than the grandsons of Gandhi. Is their icon so fragile that he can be destroyed or even damaged by a single, scholarly, book?

LikeLike

If I remember correctly, Vivekananda would appear in Sri Aurobindo’s meditation and guide him (this has to be verified).

Yes, Vivekananda had tremendous charisma.

But he had some weaknesses too. Like eating. He was a beef-eating glutton and overeating killed him.

His Neo-Vedanta theories have done Hinduism great harm and it is only now that Hindu thinkers are trying to correct the wrong impressions about Hindu Dharma that he passed on to his foreign friends and to Hindus at home in India. It should be remembered that he is the founder of that anti-Hindu institution called the Ramakrishna Mission.

LikeLike

What Did J.D. Salinger, Leo Tolstoy, and Sarah Bernhardt Have in Common?

The surprising—and continuing—influence of Swami Vivekananda, the pied piper of the global yoga movement.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303404704577305581227233656.html

Two extracts from the article which speak volumes of Vivekanands greatness

‘He is the most brilliant wise man,’ Leo Tolstoy waxed. ‘It is doubtful another man has ever risen above this selfless, spiritual meditation.’

“Scores of women walked over benches to get near him, prompting one wag to crack, if Vivekananda ‘can resist that onslaught, then he is indeed a god.’

LikeLike

Aurobindo was great , but he was not in the Vivekanand mould of a sanyasi. Aurobindo as you have said was like a Rishi, For example Vishwamitra had to overcome so many obstacles to be called as a Brahamrishi by Sage Vashista. There were many Rishis like Vishwamitra. There is even a parable if you call it that way that Lord Shiva had to come as a mendicant to quell the arrogance of the learned at Chidambaram.

Sanayasa is the highest form of Bairagya. It is not an easy path to follow which Acharyya Sankara very eruditely presented in Vivekachudamani , which is path of negation ( neti, neti). The Path of affirmation of Bhakti is for the householder. Many Rishis in the days of the yore have done Tapas and lived as householders. Rishi Vashista wife was Arundhati. Vivekachudamani a difficult text to understand is a must for all seekers or sadhaks as it delineates affirmation and negation beautifully.

LikeLike

Sri Aurobindo is recognised as a modern rishi in the mould of the ancient Vedic rishis. The ancient rishis passed through many visitudes, overcame all obsticals, and were victorious in the end. This was also a great victory for Dharma and an example for all of us to follow.

Demanding that Sri Aurobindo be recognised as an avatar is childish and exposes the fanaticism of zealous believers campaigning against author Peter Heehs. Charging him with blasphemy is ridiculous! There is no concept of blasphemy in Hindu Dharma. So what are these misguided devotees: Jihadis? Crusaders?

LikeLike